Named for President Theodore Roosevelt, these dark brown ungulates are the largest subspecies of elk in North America, with bulls sometimes reaching 1,100 pounds and cows more than 600 pounds. The park houses the largest wild herd of Roosevelt elk left in the Pacific Northwest, which is probably the reason they are also called “Olympic elk.” No trip is complete without observing these iconic animals, and your chances of spotting them are good.

If you witness an aggressive elk, take note of the location and report it to a park ranger as soon as possible.Olympic National Park was originally organized to protect the Roosevelt elk and provides both summer and winter habitat for them.

Make noise, so that your new position remains known to the elk. Drop a backpack or jacket in front of you to act as a distraction and “barrier” between you and the elk. Make noise, so that your position is known to the elk. Avoid direct eye contact, walk widely around the animal(s) if possible, keeping it in view, watching for signs of aggitation (tongue flickering, head lowering, pawing the ground). If you encounter a bull with his harem on a trail, slowly back away and find an alternative route. They may stomp and charge at both people on foot and vehicles. At this time bulls gather their cows in groups, or harems. A single cow or groups of cows with calves should be given a very wide berth, as tempting as it may be to try to get that great photo of a newborn calf!ĭuring the fall rut, or elk breeding season, in late August through October males (bulls) become defensive and aggressive. As people approach, a cow may charge aggressively, and could rear up and lash out with her front legs. Newborn elk calves may be hidden in vegetation out of view, sometimes near trails. Recommended viewing distance is 25 yards (75 feet), but for your safety, farther distances are recommended in the spring and fall.ĭuring calving season, late May through June, female (cow) elk may be extremely defensive of their young. Photo / National Park Service Roosevelt Elk SafetyĪs the largest subspecies of North American elk (bulls can weigh as much as 1,200 pounds), Roosevelt elk are a majestic sight, but can pose hazards depending on the season. Park staff respond to any reports of close encounters between elk and humans. They may be encountered in virtually all habitat types including forests, prairies, along Redwood Creek gravel bars, and on the beaches.Įlk management in Redwood National and State Parks mainly consists of keeping track of herds seasonally, especially during calving season (late May through June), and during the fall rut (late August through October), when elk are more likely to become aggressive toward humans. In Redwood National and State Parks, Roosevelt elk may be seen anywhere from Freshwater Lagoon to just south of the Klamath River and north of the Klamath near Crescent Beach and Crescent Beach Education Center. The other herds range in size from approximately 10 to 50 animals. The Bald Hills herd is by far the largest in parks, numbering around 250 animals. By 2018, an elk herd had moved into Orick, CA.

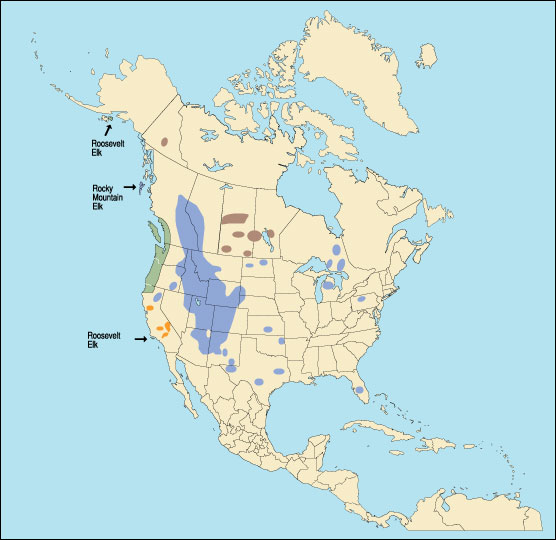

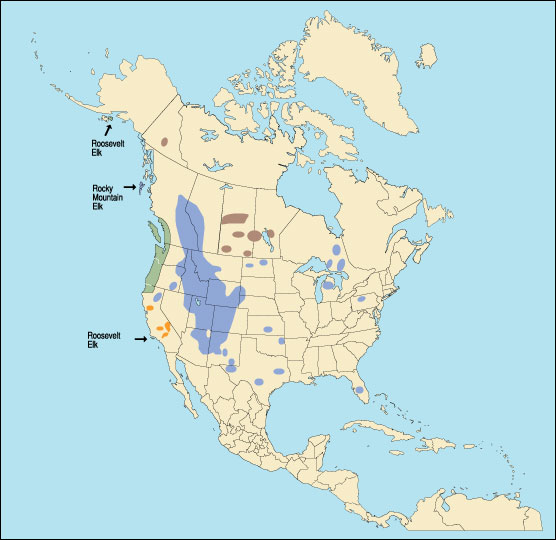

General herd locations are the Crescent Beach area, Gold Bluffs Beach and Prairie Creek Redwoods State Park, Elk Meadow, Lower Redwood Creek, park lands in the Orick Valley, and the Bald Hills. Seven elk herds call Redwood National and State Parks home, although at times these herds become loose aggregations of smaller groups. Today Roosevelt elk in California persist only in Humboldt and Del Norte Counties, and western Siskiyou County. The Roosevelt elk ( Cervus elaphus roosevelti ), is the largest of the six recognized subspecies of elk in North America they once occurred from southern British Columbia south to Sonoma County, California. Photo / National Park Service Roosevelt Elk

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)